Pappus's theorem

In my Calculus II class, we were talking about solids of revolution, and how calculus allows us to pretty easily solve a suite of problems that the Greek philosopher-mathematicians spent a lot of time thinking about (mostly because it was economically useful to have accurate computations of the volumes of pithoi and amphorae, both of which are solids of revolution). I mentioned something about how Archimedes had solved a special case (the volume of a paraboloid), and that there was some other guy who did something cool in this regard, but I couldn't pull the name immediately.

The other guy is Pappus of Alexandria, and in modern language, Pappus's theorem1 goes like this: Say you have a plane figure $F$ which you are revolving around an external axis. The volume $V$ of the solid thus swept out is equal to the product of the area $A$ of $F$ and the distance $d$ traveled by the centroid (aka center of gravity) of $F$:

In historical context this is maybe one of the crowning achievements of any Greek geometer not named Euclid. With the tools of calculus, this becomes a pretty straightforward problem that you could reasonably give to an undergraduate. In particular:

There's a special case that's straightforward

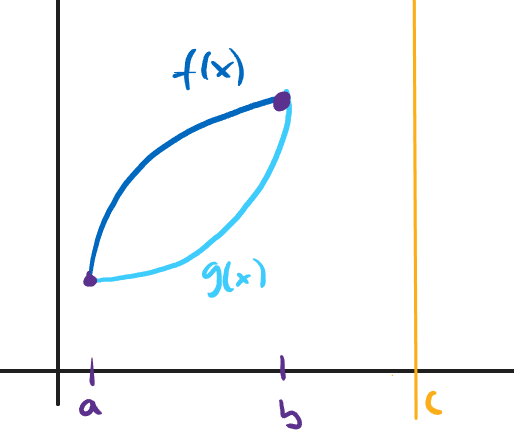

Say that your setup is like this:

To describe this in words, $F$ is bounded by two functions $f$ and $g$, where $f$ is the upper edge and $g$ is the lower edge. These functions intersect at $x=a$ and $x=b$, and we're rotating around the axis $x=c$ (for “center”), where $a < b < c$.

We're going to calculate the volume in some reasonable way (ie. the method of shells), and we're going to calculate the product of the area of the region and the distance traveled by the centroid, and show that those are the same.

Calculating the volume

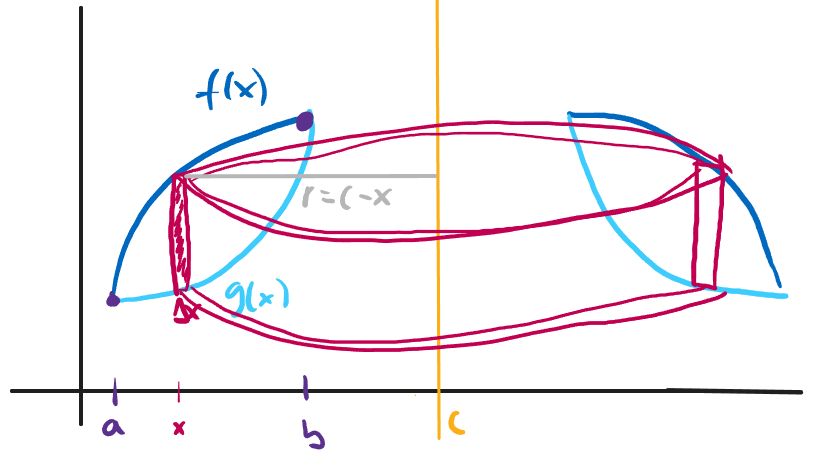

The method of shells gives you a straightforward way to calculate the volume of the solid of revolution: Draw a vertical slice of this region and revolve it around the axis $x=c$. What you get is something like the skin of a tin can. The height of that slice is $f(x) -g(x)$, the thickness is $\Delta x$, and the circumference is $2\pi r$, where $r$ is the (horizontal) distance between the slice location and the center of revolution $c$. Looking at this picture will show you that $r = c-x$:

(My art is very beuatiful and very accurate. This is a math blog, not a drawing blog.)

Imagine cutting this big tin can open and unrolling it so it lies flat. You therefore have a rectangular slab, whose volume is length times width times height: $[2\pi(c-x)][f(x)-g(x)]\Delta x$. Therefore, the volume is:

Finding area times distance

Now let's make sure that Pappus's formula works out to the same thing. We'll need to find the centroid, but we don't care about the $y$-coordinate of the centroid because it won't be moving in the $y$ direction and we only care about the distance it travels.

The centroid of a system of point masses is the weighted average of their locations, with weights given by, uh, their weights:2

Let's think about discretizing our region by, again, cutting it into vertical strips.3 To calculate the weight of such a strip, I probably want to multiply a density by an area; I don't have a given density here so I'm going to act like it's 1 (in whatever silly units) and just say that the weight of a strip is basically its area. A strip is approximately a rectangle, so its area is height times width: $A_\text{strip} = [f(x)-g(x)]\Delta x$. Passing to integrals,

Notice that denominator is in fact the area of the region.

So then the distance the centroid travels is the circumference of the circle it describes. The radius of that circle is $c-\overline{x}$. So,

Yay, $A\cdot d$ is indeed equal to $V$ that we calculated by other means.

That was a fair amount of work, but I think you could reasonably give this to an undergrad somewhere in the middle of a second-semester calculus class. Which is cool! It's kind of amazing that the machinery of calculus is so powerful that we can give it to a teenager and they can achieve something that was the crown jewel of Greek geometry.

However,

that is certainly not how Pappus did it (he did not have the machinery of calculus), nor how he even stated the theorem. So what was his whole deal?

Watch for Part 2 of this series of posts!

-

I should be slightly more careful and call this Pappus's centroid theorem, because there's another pretty useful theorem due to Pappus that comes up in geometry. ↩

-

If you don't believe this and you are a physics person, write out the equation that says that the total torque about $\overline{x}$ should be 0: $\sum w_i (x_i - \overline{x}) = 0$. Then solve for $\overline{x}$. ↩

-

If I was being very careful I would write this as a double integral, but I'm going to handwave this by again noting that I only care about the $x$-coordinate. ↩