A card activity in Calculus 2

Yesterday I was scheduled to teach my Calculus 2 class about the Second FTC at 10am, so of course I had a great idea for an activity at approximately 9:48am.

The mathematical content

To explain the activity, I must first detour to talk about my perspective on the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus, which consists of the following two parts:

- Suppose that $f$ is a continuous function on the interval $[a,b]$, and say that $F$ is any antiderivative of $f$. Then

- Suppose that $f$ is a continuous function on the interval $[a, b]$, and let $c\in[a,b]$. Then $f$ has a unique antiderivative $A$ that satisfies $A(c) = 0$, which for any $x\in[a,b]$ is given by the rule

At first glance it is not entirely clear what these two statements have to do with each other. However, with a little bit of relabeling, you can write:

Then the moral of the story becomes clearer: differentiation and integration are (almost) inverse processes.1

What this relabeling makes murkier, though, is that the role that the function we're calling $f$ is different in those two statements. In the statement on the right, $f$ is the integrand, but in the statement on the left, the integrand is actually $f'$. There is, therefore, a second and deeper moral to this story, which is that the relationship between a function and its derivative is the same as the relationship between an antiderivative and a function.

The first and second derivative tests

The first derivative test is a statement about the relationships between a function and its derivative, which I'll summarize in the following little table:

Now, the second derivative test is a recognition that the relationships between $f'$ and $f''$ should be the same as the relationships between $f$ and $f'$, since $f''$ is just the derivative of $f'$:

I'm then just introducing two new words about this and smushing these two tables together:

The moral of yesterday's class, and the secret moral of the FTC, is that we can play one more relabeling trick: if $G$ is an antiderivative of $g$, then all the same relationships in this table hold when we replace $f$ by $G$, $f'$ by $g$, and $f''$ by $g'$:

By thinking about these two tables of relationships2, you can write a bunch of sentences like “when $f$ is concave up, $f'$ is increasing” and “when $F$ is positive, $f$ is increasing” and “$F$ is concave down when $f'$ is negative.” The problem is that these sentences are word soup and it's hard to decide which ones are true without thinking really hard about them. For instance, did you notice on first read that one of those sentences was actually wrong?

The activity

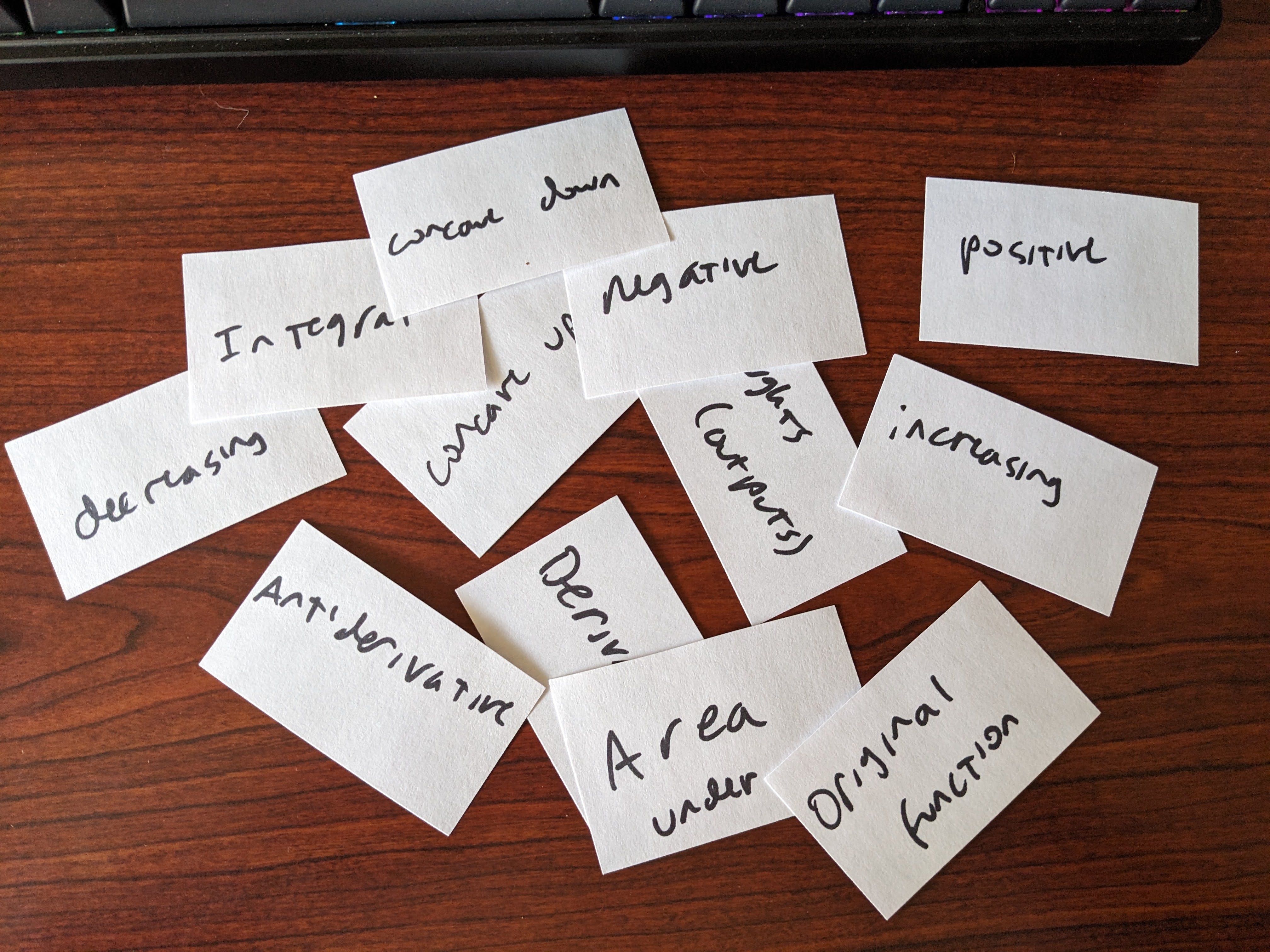

So then here is the fun activity I thought of approximately 12 minutes before class: What if I made a grip of little cards that you could shuffle around and arrange into different sentences and then decide if the sentences were true? I grabbed some index cards and a sharpie and headed off to class.

For reference, here's the list of terms I ended up writing down: integral, antiderivative, original function, area under, heights (outputs), increasing, decreasing, positive, negative, concave up, concave down.

Because I was flying by the seat of my pants here, I had to improvise what the directions were. Here's what I came up with:

- Arrange these cards into math sentences.

- This happened in small groups and maybe went for five or ten minutes.

- While I was walking around, I kept hearing things like “the area of the derivative,” which is when I decided to add the word “under” to the card that originally just said “area.”

- Another thing I noticed while walking around was that people kept doing the thing where they were rapidly looking back and forth between the cards and the derivative-tests table that they had previously written on the whiteboards.3 Success!!

- Write “several” of these sentences on a whiteboard4.

- I told people to be sure to include some correct sentences and some incorrect ones, which drove them back to their small groups to be wrong on purpose.5

- As they were writing their sentences on the board, several people started by tagging them as correct or incorrect, so I hastily added the direction to not tell me which was which, because I knew I wanted step 3 to be

- Go look at a different group's board and assess their sentences.

- In particular, I told people to write a few sentences explaining why the wrong-on-purpose one was wrong.

This activity was really fun, and in particular we had a great discussion about one group's wrong-on-purpose sentence: “The integral of the derivative is the original function.” The reason this sentence is wrong is precisely the first moral of the FTC, which I was very stoked to see emerge from an activity that I wanted to hit the second moral of the FTC.

This activity also set the stage for the wrap-up discussion: at the beginning of class, a student asked, “what's the difference between 'integral' and 'antiderivative'?” I told them that I wanted them to re-ask the question at the end, and then we had a nice discussion about definite vs indefinite integrals, which leads nicely into next week's classes about $u$-substitution and integration by parts.

Lessons for next time

I told my people at the outset of this activity that I had just thought of it and would therefore appreciate their feedback about how it went. Here are a few things they said:

- They would have liked to have a card that said “second derivative”. (I'm diffident about this because I wanted to emphasize the $G-g-g'$ version of the table rather than the $f-f'-f''$ version.)

- They would have liked to have several copies of some of the cards, in particular the “original function” card. Maybe another way to address this is to say “you can fill in missing words in appropriate ways.”

- They said this helped them see that thinking about the table was more useful than memorizing particular sentences. Again: Success!!

If you try this in your class, I'd be interested in hearing what modifications you make, and how it goes!

-

The “almost” here is an acknowledgement that the derivative kills additive constants, and therefore the integral must produce a family of antiderivatives that differ by additive constants. In other words, the derivative has a nontrivial kernel, so by Noether's isomorphism theorem, functions that are derivatives are actually (isomorphic images of) cosets of functions.6 ↩

-

Which are, again, the same table. ↩

-

I privately call this “chicken-pecking” because the head-bobbing motion that results looks like a chicken eating grain, lol. ↩

-

Anymore, I refuse to teach in rooms without whiteboards, aka vertical non-permanent surfaces, on as many walls as possible, and every class I am having people do stuff on them. ↩

-

I think that being wrong on purpose is an extremely useful way to destigmatize mistakes and promote metacognition. Probably there is a whole nother blog post to write about this. ↩

-

This is the kind of deranged sentence you write when you are simultaneously teaching calculus 2 and abstract algebra. ↩