Activity 3.2.1.

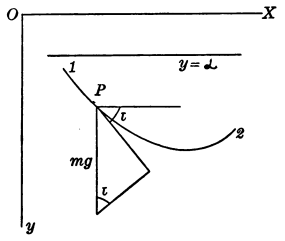

I’m hiding the diagram included in the textbook under a little foldy thing. I encourage you to draw your own diagram first, based on the instructions in the next paragraph, and then compare your diagram to the one in the book. (This will actually help you make sense of the book’s diagram when you see it, because there’s some things that aren’t super clear.) Label the following:

-

the curve of descent \(C\) connecting point 1 and point 2;

-

the vertical and horizontal components of that tangent line;

-

the angle \(\tau\) between the horizontal and the tangent line; and

-

the downward force of gravity \(mg\text{.}\)