Section 3.1 The brachistochrone problem: its significance as an illustration

The brachistochrone problem is historically the most interesting of all the special problems mentioned in Chapter I since as we have there seen it gave the first impetus to systematic research in the calculus of variations. Since the time of the Bernoulli brothers it has been used with great regularity as an illustration by writers on the subject, and it is in many respects a most excellent one. Unfortunately in the forms originally proposed by the Bernoullis it does not require the application of an important necessary condition for a minimum which was first described by Jacobi in 1837, more than a century after the calculus of variations began to be systematically studied. A special case of this condition is the restriction on the position of the center of curvature in the problem of finding the shortest arc from a point to a curve, as described in the theorem on page 33 of the last chapter. It is perhaps at first surprising that the significance of such a simple instance of the condition escaped the early students of the calculus of variations, but a study of the older memoirs soon impresses one with a realization of the serious difficulties encountered with the methods originally used. Throughout the eighteenth century, investigators in the calculus of variations for the most part desisted when they had found the forms, or in many cases the differential equations only, of the minimizing curves which they were seeking.

It is natural at first sight to suppose that a straight line is the path down which a particle will fall in the shortest time from a given point 1 to a second given point 2, because a straight line is the shortest distance between the two points, but a little contemplation soon convinces one that this is not the case. John Bernoulli explicitly warned his readers against such a supposition when he formally proposed the brachistochrone problem in 1696. The surmise, suggested by Galileo’s remarks on the brachistochrone problem, that the curve of quickest descent is an arc of a circle, is a more reasonable one, since there seems intuitively some justification for thinking that steepness and high velocity at the beginning of a fall will conduce to shortness in the time of descent over the whole path. It turns out, however, that this characteristic can also be overdone; the precise degree of steepness required at the start can in fact only be determined by a suitable mathematical investigation.

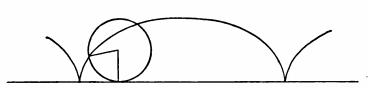

The first step which will be undertaken in the discussion of the problem in the following pages is the proof that a brachistochrone curve joining two given points must be a cycloid. We are familiar with the cycloid as the arched locus of a point on the rim of a wheel which rolls on a horizontal line, as shown in Figure 3.1.1. It turns out that the brachistochrone must consist of a portion of one of the arches turned upside down, and the line on the under side of which the circle rolls must be located at just the proper height above the given initial point of fall.

When these facts have been established we are at once faced by the problem of determining whether or not such a cycloid exists joining two arbitrarily given points. Fortunately a modification by Schwarz (1845-1923) of a method due to the Bernoulli brothers will enable us to prove that two points can always be joined by one and but one cycloid of the type desired.

When these results had been attained the eighteenth-century student was content with his progress, but we cannot be so easily satisfied because we know that in other problems of the calculus of variations further conditions on the minimizing arc are required which are quite different in character from those which have so far been described. Our doubts for this particular problem will be removed, however, by a so-called sufficiency proof which will definitely establish the fact that the time of descent from a given point 1 to a given point 2 on a suitably chosen cycloid is shorter than that on every other curve joining those two points. The method used is again that of Weierstrass, a special case of which we have already considered in Section 2.6 of the last chapter. The argument there given and the one which we shall see in the case of the brachistochrone are excellent illustrations of the type of proof which is effective for more general problems of the calculus of variations.